Why I measure BODY COMPOSITION

and we don’t fixate on kilograms on the scale

I hope you had a glorious Christmas and are enjoying some well earned rest.

It’s an appropriate time to discuss Body Composition as clients tend to fixate on weight on the scales at this time of year.

Although obesity can be unhealthy, research shows people can have metabolic dysfunction no matter their weight.

Here’s what we know about the complex relationship between body weight, body composition and metabolic health.

I am far more interested in your healthy composition which can shift dramatically during different life cycles. Let’s review what’s important and don’t skip the section on PHASE ANGLE !

When I measure body composition I am reviewing you as a whole:

The simple most common mistake I see people doing is using their scale as a measure of their weight loss or health success.

Weight and Height

Body Mass Index (BMI)

Total Body Fat

Visceral Fat (tummy, organ fat)

Total Body Water (intracellular and extracellular)

Muscle mass. Skeletal Muscle mass

Bone Mass

Sarcopenic Index (are you eroding your muscle stores)

Metabolic Age

This gives us a great baseline to work from and calculate your targets.

BMI, is a common measure of obesity and is criticized for its inability to differentiate between fat and muscle mass, fat distribution and can misrepresent health risks.

BMI doesn't show body‑fat percentage. It only uses your weight and height so it can't tell fat from healthy muscle (a very muscular athlete might be labeled obese). It also doesn't separate subcutaneous from visceral fat. Body‑fat amounts and where they are stored do a better job of predicting cardiometabolic health risk than BMI.

Central obesity (or visceral adiposity) as characterised by fat accumulation around the waist, poses a higher risk for metabolic diseases than overall obesity, making waist-to-hip ratio (WHR) a preferred metric for assessing health risks.

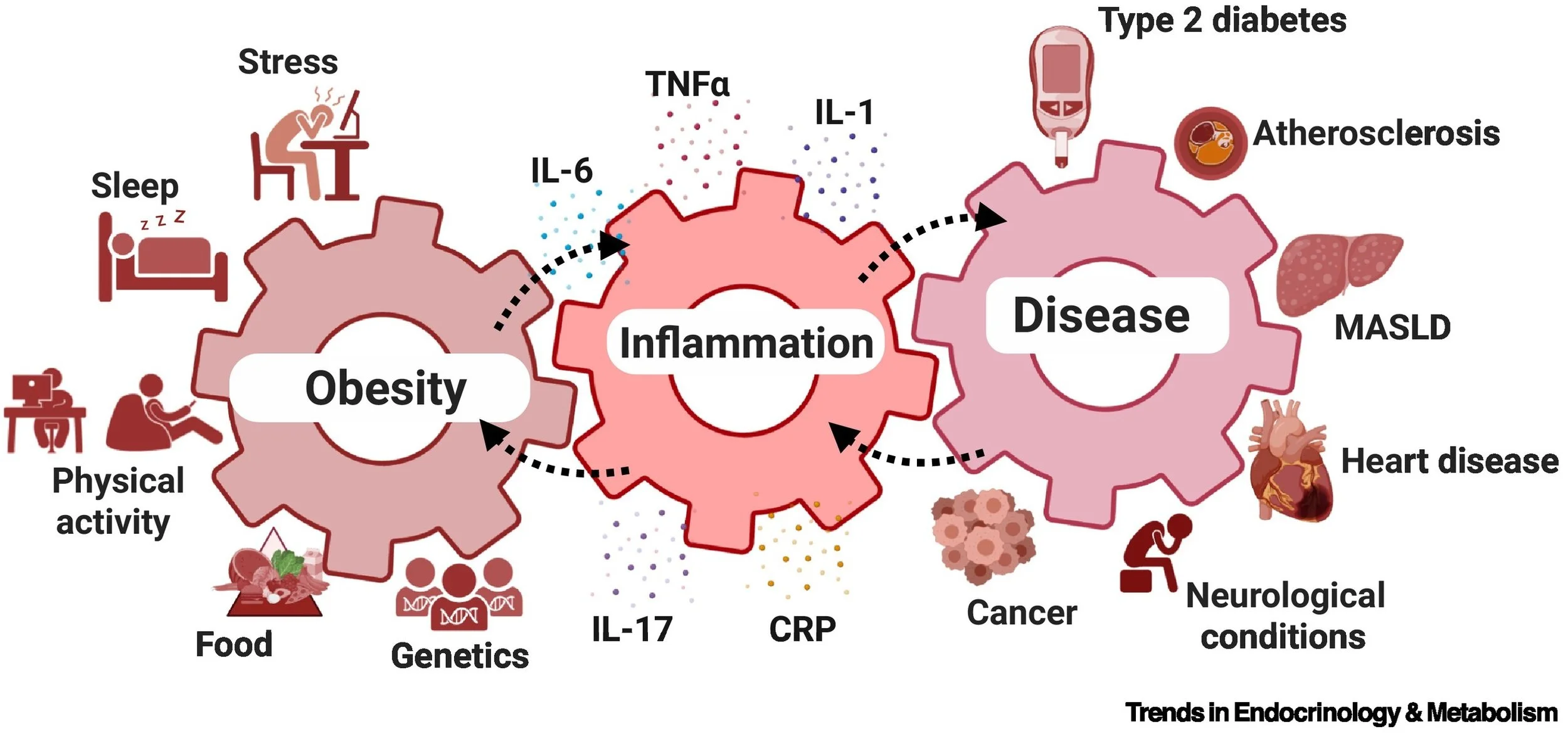

While obesity is strongly associated with conditions like Type 2 diabetes, heart disease, and certain cancers, factors such as genetics, body fat distribution, and lifestyle are significant contributors to metabolic health outcomes.

Body Composition Analysis (BIA) goes beyond weight on the scales by providing insight into how much of your body is made up of lean mass (like muscles and organs) versus fat mass.

Understanding your body composition helps assess your overall fitness and health, as having a higher proportion of lean mass typically indicates better metabolic health, strength, and longevity, while a higher fat mass can be linked to various health risks.

By focusing on body composition, not just the scale, you’re setting yourself up for improved long-term health

How to Measure Body Composition

Dexa Scan is the gold standard

DEXA scans are one of the most accurate methods for measuring body composition. They use low-level X-rays to differentiate between bone mass, lean muscle mass, visceral (organ) fat, and fat mass, providing a comprehensive picture of your body’s makeup.

Bio Impedence analysis also provides and excellent score of your composition and is easily tracked in clinic.

2. Measuring Tapes

While not as detailed as a DEXA scan, I use Bio Impedence Analysis and a measuring tape to provide a good idea of changes in body composition over time. Measuring tapes can track key areas like the waist, hips, and thighs allowing you to monitor fat loss and muscle gain. However, this method doesn’t distinguish between muscle and fat, so it’s best used alongside other methods.

• Women: A waist circumference of 80cm (31.5 inches) or more indicates increased risk of conditions such as Type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease and metabolic syndrome, while 88cm (35 inches) or more signifies a high risk. (World Health Organisation guidelines)

• Men: A waist circumference of 94cm (37 inches) or more indicates increased risk, while 102cm (40 inches) or more signifies a high risk.

3. What can my scales tell me ?

These can be misleading, as they don’t differentiate between muscle and fat.

For example, if you’ve gained muscle and lost fat, the scale might not show a change, even though your body composition has improved and your starting to look more toned!

To get a more accurate assessment, consider a BIA that measures body fat percentage, muscle mass, and other metrics.

Muscle is your Biomarker for Longevity

Your muscular system is a key player in your metabolism, storing amino acids, and combating inflammation. According to many studies, muscle mass is an agreed predictor of longevity especially in older adults.

Greater muscle mass not only reduces fragility and supports your metabolism but also offers a variety of other health benefits:

· Improved Metabolic Health: Muscle mass significantly impacts metabolic health by enhancing insulin sensitivity, glucose utilisation, and fat metabolism

· Prevention of Sacropenia: Building and maintaining muscle mass helps prevent sarcopenia, the age-related decline in muscle, which is associated with frailty, falls, and increased and early mortality in older adults.

· Lowers Inflammation: Myokines, which are signalling proteins released by muscles during exercise, have anti-inflammatory effects and help regulate the immune response.

· Improves heart health: More muscle boosts metabolism, helping control blood sugar and cholesterol, which reduces heart disease risk. It increases insulin sensitivity, reduces body fat—especially harmful belly fat tied to inflammation—and helps regulate blood pressure.

· Increased Resistance to Injury and Illness: During periods of illness or injury, the body requires additional resources for healing and repair. Having a greater muscle mass provides a reservoir of amino acids and other nutrients that are crucial for the recovery process. This reserve helps maintain overall strength and energy levels, facilitating faster recovery.

· Improved Immunity: Muscle mass supports the immune system by providing amino acids necessary for immune function, which can help in recovery from illness and injury.

Protein matters — especially when you’re trying to build or keep muscle.

I see people in clinic often unintentionally under estimating their protein needs, so here’s a simple, friendly reminder of why it matters:

Protein helps maintain and grow muscle. More muscle isn’t just about strength or looks — muscle burns more calories at rest than fat, so preserving or building it supports your metabolism in a very healthy way.

Digesting protein uses more energy than carbs or fat. That “thermic effect” means eating protein gives a small metabolic boost because your body works harder to break it down.

Protein also plays a role in important body processes like hormone and enzyme production and detoxification, which helps keep your metabolism running smoothly.

Quick tip: Aim for about 1–1.5 g of protein per kg of body weight daily. So if you weigh 70 kg, target roughly 70–105 g of protein each day.

3 Simple Strategies to Start Building More Muscle

Prioritise Strength Training

Engage in regular strength training exercises, such as weightlifting, resistance band workouts, or bodyweight exercises like push-ups and squats. Aim for at least two to three sessions per week to effectively build and maintain muscle mass. If you're new to this, invest in a few months of personal training.

Optimise your Protein Intake

Ensure you’re consuming enough protein to support muscle repair and growth. Include a variety of protein sources in your diet, such as lean meats, fish, eggs, legumes, and dairy. Consider supplementing with protein smoothies, especially post-workout, to give your muscles the nutrients they need to recover and grow stronger.

Focus on Progressive Overload

Gradually increase the intensity of your workouts by lifting heavier weights, adding more reps, or incorporating more challenging exercises.

And last, a word on Phase Angle

Phase angle (PA) is an important parameter measured during bioelectrical impedance analysis (BIA), and gives me so much insight into your current state of wholistic health. It is used a lot in the US but in a limited way by local practitioners.

It is a reflection of :

cellular energy

cellular integrity

function.

High phase angle: = stronger, healthier cells;

Healthy, intact cell membranes

Good cell mass

Proper hydration

Often seen in athletic or well-nourished individuals

Low phase angle: = compromised cellular health.

Damaged or less intact cell membranes

Lower cell mass (muscle wasting)

Malnutrition, chronic illness, or aging

Can indicate increased extracellular water relative to intracellular water…puffiness, oedema, retained lymph.

How do I use phase angle ?

Nutrition and malnutrition: I use PA as an early marker for malnutrition before weight loss becomes evident.

Disease prognosis: In conditions like cancer, liver disease, kidney disease, or HIV, a lower PA has been linked to worse outcomes.

Athletic and wellness monitoring: Allows me to track changes in muscle mass and cell integrity over time.

Hydration assessment: Helps detect fluid imbalances (e.g., overhydration vs dehydration) indirectly.

Typical reference ranges

Generally, healthy adults have a PA between 6 and 7°, but this varies by age, sex, and population.

Values <5° often suggest poor cellular health or malnutrition.

Values >7° are generally seen in athletes or very healthy individuals.

Body Composition analysis and interpretation forms part of every Initial Functional Health Intake consultation and is revisited over time as your health improves.